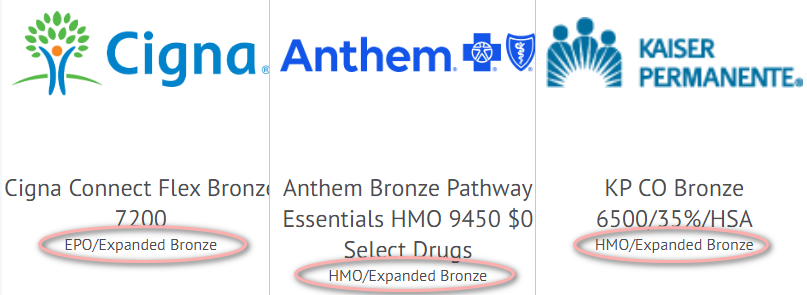

An interesting new study by The Commonwealth Fund finds that more than half of Americans who are covered by individual health insurance have policies that would not meet the minimum requirements for being sold in the health insurance exchanges that will be operational as of 2014. Starting in January 2014, all health insurance plans sold in the exchanges – as well as non-grandfathered plans sold outside of the exchanges – will have to meet basic standards of at least “bronze” level coverage (policies will be classified as bronze, silver, gold, or platinum, depending on what percentage of costs they cover). But an analysis of the existing plans in the individual market has found that 51% of them are so-called “tin” plans, that do not have the minimum level of coverage that will be required of new plans beginning in 2014. In contrast, less than 1% of people covered by group health insurance have “tin” plans.

I have no doubt there will be some improvements in the quality of individual health insurance once the bulk of the ACA takes effect in another year and a half (assuming that the law doesn’t get overturned by the Supreme Court next month). But I think there are a few things that have to be kept in perspective when we look at this study, or any other that compares individual and group health insurance.

Price is the major issue. The data presented by the Commonwealth Fund study is correct: people with individual health insurance incur higher average out-of-pocket expenses than those with group plans ($4,127 was the household average out-of-pocket expense for families with individual health insurance, versus $1,765 for families with group coverage). But if we consider the price of the coverage in the equation, the end result looks a lot different.

In Colorado, the average private-sector group health insurance premium in 2010 for a single employee was $4,630. For an employee who was enrolled in family coverage, the average was $13,393.

Nationally in 2010, average individual premiums for a single person were $2,004 and for a family they were $4,704.

That’s a pretty significant difference. Yes, the group policies have lower average out-of-pocket exposure and tend to include coverage that is often optional in the individual market (maternity, for example). But the average premium for group coverage for a family in Colorado in 2010 was almost three times the national average for family coverage purchased in the individual market.

Of course, a significant chunk of the premiums is usually paid by the employer. But that’s not free money. If health insurance were less expensive, employee wages would likely be higher – the money has to come from somewhere, whether it’s paid directly from the employee in the form of payroll deduction, or by the employer.

Individual health insurance, however, is generally funded entirely by the insured (I say “generally” because Colorado Senate Bill 19 that passed in 2011 allows employers in Colorado to fund individual health insurance within a framework of regulations designed to prevent an exodus from the small group health insurance market). When people are paying for their own health insurance, they have a strong incentive to shop around. And people will often gravitate towards lower-cost policies with higher out-of-pocket exposure in an effort to keep the premiums as low as possible. This strategy can be financially dangerous if the insureds don’t have money set aside in an HSA or other savings account to cover out-of-pocket expenses. But even so, the premiums that a family has to pay every month are often the most important part of the deal, and people look for what they can afford.

So although it’s true that out-of-pocket costs are higher in the individual market (likely due in large part to people opting for policies that are less expensive), if we combine the premiums and the out-of-pocket costs, the total expenses are lower in the individual market ($8,821 in the individual market versus $15,158 in the group market, using Colorado private sector family premiums for the group data). To ignore cost when comparing the policies is to leave out a large piece of the equation.

The Commonwealth Fund study mentions maternity coverage as an example of a benefit that is often not included on individual policies, thus earning them a “tin” rating. In Colorado, maternity is now included on all policies that have been issued or renewed since January 2011 (the data for the study was collected in 2010). But in many states, maternity coverage in the individual market is rare and/or quite expensive as an optional rider. This will change in 2014, and based on our observations of the Colorado individual market over the past year and a half, I would say that the change will be a positive one. But given the fact that so many individual policies did not include maternity coverage in 2010, I’m curious as to what percentage of individual health insurance plans would have earned at least a “bronze” ranking if maternity had been excluded from the data. If we don’t count maternity, how do individual health insurance plans measure up? Most individual plans (assuming they aren’t mini-meds or some sort of limited benefit coverage) in Colorado in 2010 covered complications of pregnancy and charges incurred by a newborn (eg, a premature baby who is in NICU for weeks). But routine maternity care was included on very few individual plans in Colorado prior to 2011. Given that fact, and the fact that all new individual plans in Colorado now have maternity coverage, I’d be curious to see how individual and group plans compare in 2012.

Overall, I think that The Commonwealth Fund study is a good one. It highlights the out-of-pocket exposure that people have in the individual market, and it’s true that the average plan in the individual market has higher out-of-pocket exposure than the average plan in the group market. But to make the comparison without also looking at the premium costs in each market seems a bit disingenuous. If individual health insurance were two to three times as expensive as it is now, it could cover more costs for members with less cost-sharing. But that doesn’t seem like a good solution either.